Communication and Leadership

At the end of my first year of graduate school, I received an envelope from one of my professors. I opened it and found a written assessment of my performance that semester. My professor wrote that my written work was below average; that it suffered because I tried to write something memorable or original, instead of just writing what I meant; and that my search for “a novel turn of phrase” too often came at the expense of presenting a clear and simple idea.

It was hard for me to accept that I wasn’t a good writer. I did well on my written work at the Naval Academy, I edited a magazine, and I even published a few articles. I was proud of my ability to communicate. But my professor was right; my writing was not persuasive. I tried too hard to be creative, and most of the time I didn’t present clear ideas. I often wrote sentences because I liked the way they sounded, or just because they were clever.

It wasn’t until seven years later that I began to understand how much I needed to improve as a writer. In 2009, a close friend told me that the speechwriter for General David Petraeus was rotating to her next assignment, and that I might be a good fit for her job at U.S. Central Command. I put together some writing samples and within a month I was headed to Central Command Headquarters in Tampa, Florida.

On my way down, I called a former White House speechwriter for some advice. He told me that writing for senior officials, or anyone for that matter, is like having your ego surgically removed one day, replaced the next, and then removed the day after, in a continuous cycle. He said the job of a speechwriter is especially challenging because an institution doesn’t have to face its disagreements until someone has to stand up and say something. But he also assured me that I’d be fine, “because bureaucracies rarely aim low enough to take out a speechwriter.”

On my first day at U.S. Central Command, General Petraeus told me to buy a copy of the The Elements of Style, the classic handbook on English usage by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White. He said, “There’s a mechanical side of writing, and there’s a creative side. You need to have the mechanics down cold so you can send a clear message. The idea is the most important thing. If you can find an elegant way to say it, that’s great – but elegance is always secondary to getting the idea right. Follow the rules and apply the principles in that book. I try not to deviate from them.”

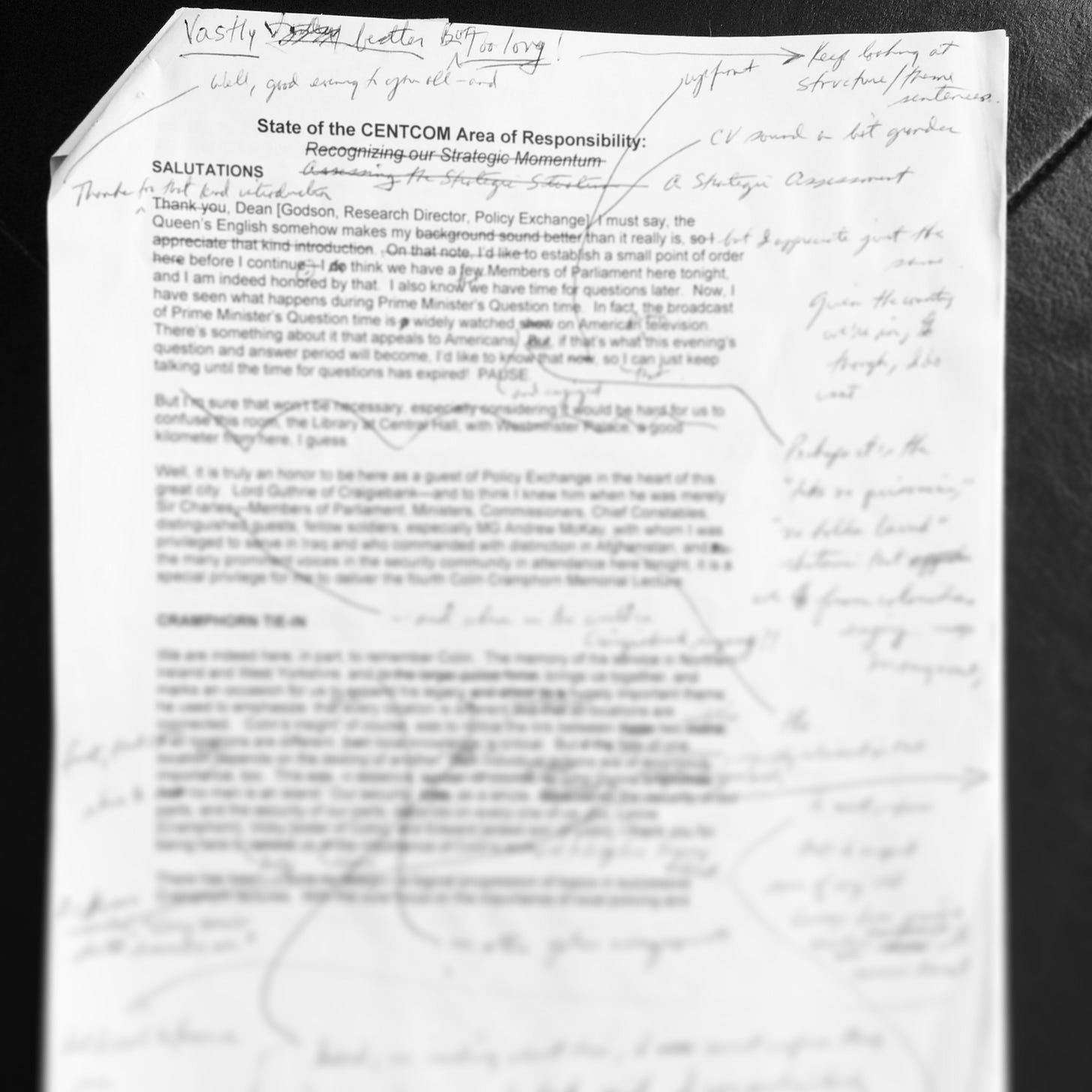

The following week, General Petraeus met with his staff to review his speaking schedule. In less than a month, he was scheduled to deliver the Colin Cramphorn Memorial Lecture, a keynote address hosted by the Policy Exchange in London. General Petraeus said the Cramphorn Lecture would be a “big, significant speech,” so he wanted a draft right away. I was assigned as the lead writer (though of course we all worked speeches as a team).

I wrote a ten-page, single-spaced speech and sent it to him for his review. He brought me into his office, pointed to the draft, and said, “I need to teach you about theme sentences. I’m not sure you know what they are. Every paragraph should start with a clear sentence that sets the theme for that paragraph. You should be able to read any theme sentence and know exactly where you are in the speech.” He gave me his hand-written edits, and we exchanged the draft another ten times before he delivered it in London.

At some point in the next few months, I printed out George Orwell’s famous essay, “Politics and the English Language.” I cut out one sentence and taped it to my desk: let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. I looked at the sentence every time I was stuck and needed to find the right thought. I lost count of how many times that simple reminder rescued me from a hopeless situation.

Over the next four years, I had the opportunity to serve as a speechwriter to General Petraeus, General James Mattis, and Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta. That experience changed my outlook on communication in three ways:

First, the mechanical act of writing speeches developed my writing ability, but the process of writing speeches has made me into a much more discerning reader and listener. I used to read articles and listen to people without concentrating on major concepts and themes, considering how those concepts were organized, and recognizing the kinds of images people used to express them. I was reading words, not playing with ideas. I should have learned to do this a long time ago, of course; after all, the critical thinking process is the fundamental goal of any liberal arts education. My point is that it’s one thing to understand the importance of critical thinking, and it’s quite another to exercise that ability as a matter of habit.

Second, the proper way to think about writing speeches is not to think about writing at all – it’s to think instead about designing a speech so that it leaves the intended message. It’s about structuring an argument, not merely writing a speech. The only way to build an argument is to go through a painful, deliberate writing process. And that writing process is part of an even more important thinking process – an unremitting cycle of studying, thinking, and writing that helps clarify and order ideas. The only possible outcome of a poor thought process is confusion. Or in other words, sloppy writing is the only possible product of sloppy thinking.

And third, I’ve learned that letting ideas speak for themselves is a constant struggle. It takes serious effort to get the big ideas right and to communicate them well. It’s even harder to build a whole argument – to express a series of clear ideas in logical order. That requires self-study, organizing your thoughts, and reflecting them back to yourself in written form – to again resolve and structure ideas in some logical order. Accomplishing these tasks is just plain hard, and there’s no avoiding them if you want a compelling product. Every time I write, I have to work hard to say what I mean, and to resist a novel turn of phrase.

But the reward for all of this pain is precision. Clear ideas resonate like sound from a tuning fork: pure, unmistakable, and irresistible. All I really learned from speechwriting can be summed up in two words: be precise. As Donald Rumsfeld once wrote about serving in the White House, “A lack of precision is dangerous when the margin for error is small.”

The admonition to be precise underlies every communication principle I learned from speechwriting. They are all variations on the same theme:

Speak only when you have something to say;

Speak such that you cannot be misunderstood;

Convey the intended ideas, and none more;

Leave the audience with an unmistakable single headline or message;

Resolve the underlying ideas so that the structure of the argument is self-evident;

Begin paragraphs with short, declarative theme sentences;

Beware the novel phrase, for it may not mean precisely what you want (e.g. kill your darlings).

But as valuable as it’s been for me learn these principles, it’s been far more important to recognize the purpose of communication. The mechanics and principles of communication are not ends in themselves, they are tools for persuasion – and our country needs leaders who use them well. Leadership requires much more than basic literacy. A great communicator expresses ideas the way a composer arranges notes, in deliberate sequence. But if the point of music is to stir emotion, then the point of communication is to inspire action.

Our system of government, in particular, depends on leaders reasoning based on good advice, independent thought, and sound judgment – and then communicating clear ideas. The point of reasoning is to decide. The point of communication is to persuade. And the point of leadership is to decide and persuade.

The end goal for any leader is to say what you mean, to state your main idea loud and clear, to be precise lest others misunderstand, and above all, to tell the truth…and the only way to do all of these is to use plain English – and if you can help it, proper grammar.